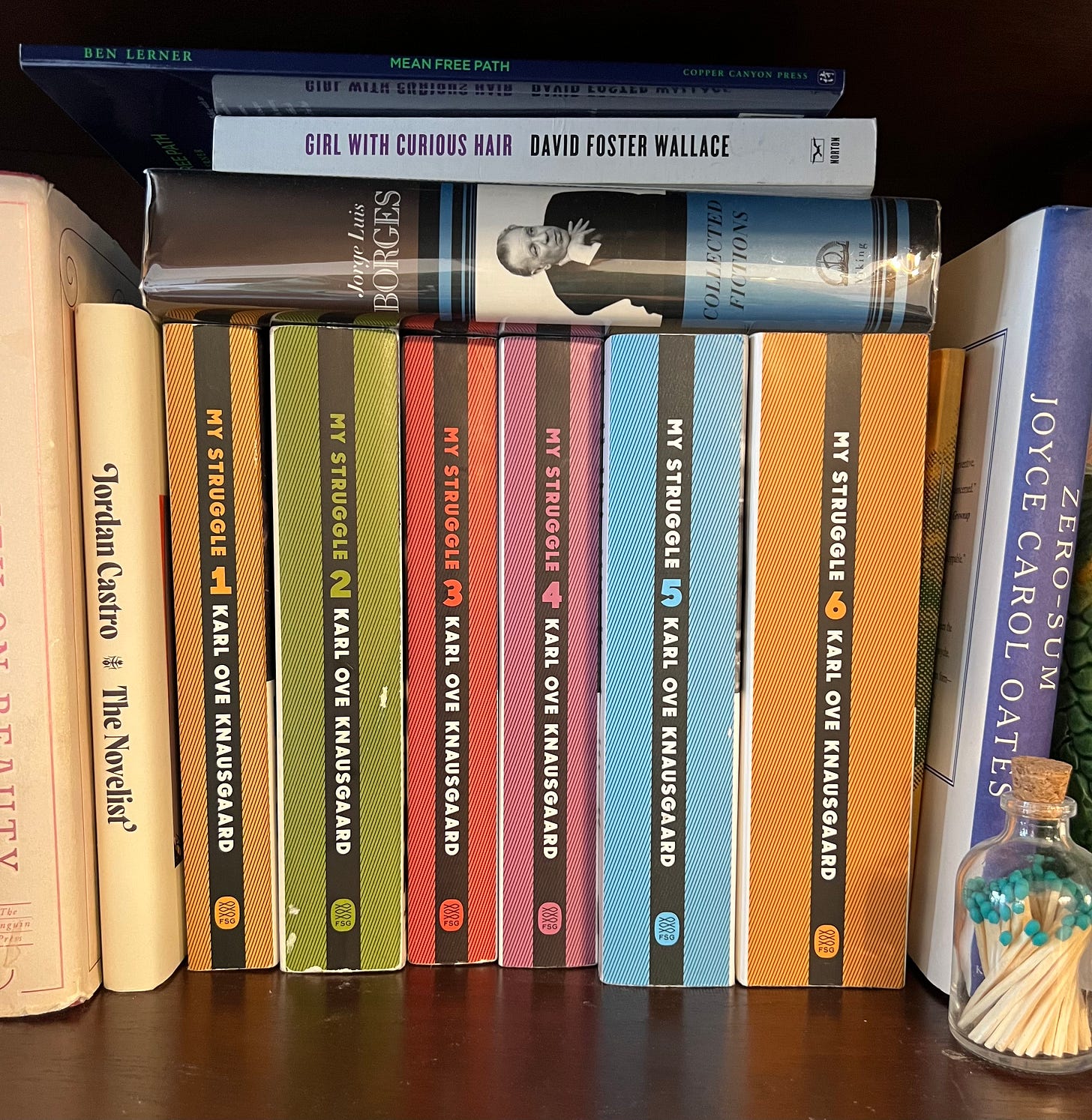

In mid-December 2023, while book shopping in Georgetown with my girlfriend, the six volumes of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle caught my eye. They were color-coded by their spines and lined up in order, mostly progressing from thin to thick: mustard yellow, green, red, purple, blue, and dandelion yellow, the thickest. It’s hard to remember where I first heard about these books—my best guess now would be Better Than Food’s review of Book 2—but, for some reason, I decided then and there that I would finally try to read them.

My Struggle, originally titled “Min Kamp,” is a nearly 4,000 page work of autofiction by Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard. It became a sensation in Norway and then in America once it was translated into English. It’s now considered one of the central texts in the contemporary wave of autofiction—a genre defined by its amorphous blend of first-person fictional construction and authentic biographical fact.

The books are each shaped around different times in Knausgaard’s life: Book 1 focuses on the death of his father; Book 2 tells of the early days in the relationship of his second wife, Linda; Book 3 describes his early childhood up to adolescence; Book 4 describes his work teaching in rural Norway after gymnas, or high school; Book 5 covers his time becoming a writer; and Book 6, written as if in the present day, describes the backlash that My Struggle 1 created in his family (and delves into a near-400 page essay on Hitler’s fascist overthrow of the German language). Each book departs from the main plot at certain points, often with acknowledgement of the present situation, in which Karl Ove Knausgaard is sitting down at his desk and writing the words we’re currently reading. But there’s no gimmicky, tongue-in-cheek, avant-garde, postmodern literary games going on here—My Struggle is about a man and the many components of his life, most of which are mundane.

Knausgaard does this masterfully. He puts his consciousness on display to such an extreme that, over the weeks and months it takes to finish My Struggle, you become consumed by it. You take the characters to be real, the setting to be real, the narrator and the author to be the same person, and when you put all those things together, even the fictional qualities, such as the constructed dialogue, appear real.

Knausgaard did all this, but he also did something else. He just about destroyed my reading habit. This essay is my attempt to describe how he did this.

Nearly every day, on my hour-long commute to and from work, I would read My Struggle. At that rate I could read about 20-25 pages well at my pace. I usually wouldn’t read after getting home, so on a standard day I’d read about 40-50 pages. The further I got in the series, the quicker I wanted to read. By the time I got to books 5 and 6, I split my time between reading the physical book and listening to the audiobook so that I could keep up with it on long car rides. To read My Struggle from start to finish, with this routine, took me about five months. By the time I finished, I didn’t really want to read anything else.

It’s difficult for me to pin down exactly what qualities in a book best capture my interest, and it’s significantly harder than that to make “objective” claims about literature’s allure more broadly. For me, there were several surface-level aspects of My Struggle that made it immediately appealing: His being a writer, his interest in art and literature, the contemporary setting in unfamiliar but fascinating cities and countries and his ability to describe them in such detail that I felt I was there. There were also some key formal qualities, like the simple yet poignant language and the robust characterizations of Knausgaard’s friends and family members, that made the books consumable.

The aesthetic value of My Struggle is the subject of debate in the literary community. Critics point to its accessibility and popularity to make the claim that it’s nothing more than a pop literature phenomenon, an overly long gossipy tell-all about one man’s life and family. (He’s certainly created public figures of himself and his family, no doubt.) Toril Moi, writing in The Point, described: “Along with the rest of the Norwegian population, I was hooked from the start…The publication schedule was addictive. Every two or three months or so, I needed my Knausgaard fix. The long wait for Book 6 was excruciating.” In Book 6, we actually get a glimpse of this phenomenon—Book 1 has already become a smash hit, and around the publicity and glamor, Knausgaard is enkindled in a legal battle with his late father’s brother. When the books were translated to English about a decade later, Britain and America had a similar wave of Knausgaard-mania.

Could the books have been so well-received in the literary community just because of their huge popularity? Well, unlike other world-famous smash literary hits, the plot of My Struggle is mostly tucked away into the background, the narrator is seemingly a pretty normal person (at least until the last book), and for every page of gossipy drama there are twenty pages of ordinary action—sitting down to write, walking through the woods, putting the kids to sleep, arguing with neighbors, etc.

In a Paris Review-published interview, critic James Wood and Knausgaard discuss the postmodern task of breaking forms to actually achieve verisimilitude, rather than depart from it. But while Knausgaard doesn’t break the form in the style of, say, John Barth or Thomas Pynchon—tearing up conventional plot, timeline, or narrative constructions—he does so for almost the opposite purpose: to make the form of the novel more visual. “Before I wrote My Struggle,” he said, “ I had a feeling that novels tend to obscure the world instead of showing it, because their form is so much alike from novel to novel.” Toril Moi notes that this subtle attention to form is missed by critics who dismiss the books as lacking literary depth because of their accessible language.

American writer Brandon Taylor has pointed out that a huge pet peeve of his is the tendency for writers to forget that they’re writing in first person and write as though “their” (the narrator’s) perceptions are perceptions of a third party. “It causes me a special pain when I read lines like I frowned or I felt my lips twitch into a grin or I could see or I could hear or I wiped sweat from my brow,” he wrote. “If you are writing in first person POV, then every object noted in the story is perceived.”

The failure of the writers Taylor describes comes from an overreliance on the visual. Writers forget that they’re writing fiction and not watching a movie or TV show, in which the central character is a distinctly separate person from the viewer. When these two modes are conflated, it becomes easy to forget that when authors are writing in first person, they are revealing the narrator’s interiority, and it only makes sense to describe externalities when they are the subject of the narrator’s focus.

It’s not so black-and-white, of course. When writers want to depict the world’s minute visuals from a first-person POV a la Knausgaard, they must be careful to blend exteriority and interiority without crossing wires. Listen to how Knausgaard blends the external and internal during this scene from Book 2, when he believes that he’s lost his future wife Linda to her friend, Arve:

Arve wasn’t there, so I went back, found him, told him what Linda had said to me, that she was interested in him, now they could be together. But I’m not interested in her, you see, he said. I’ve got a wonderful girlfriend. Shame for you, though, he said, I said it wasn’t a shame for me, and crossed the square again, as though in a tunnel where nothing existed except myself, passed the crowd standing outside the house, through the hallway and into my room where the screen of my computer was lit. I pulled out the plug, switched it off, went into the bathroom, grabbed the glass on the sink and hurled it at the wall with all the strength I could muster. I waited to hear if there was any reaction. Then I took the biggest shard I could find and started cutting my face. I did it methodically, making the cuts as deep as I could, and covered my whole face. The chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, underneath the chin. At regular intervals I wiped away the blood with a towel. Kept cutting. Wiped the blood away. By the time I was satisfied with my handiwork there was hardly room for one more cut, and I went to bed.

Taylor, who refers to Knausgaard as a “Norwegian master,” sees scenes like this as a success for visual first-person narration. If a writer were to fail in this scene, the way Taylor describes, I think they’d over-describe the narrator’s face; his immediate sensations, like the stinging pain above his forehead; maybe some trivial details in the room, like the bathroom floor tiles or specs of dust on the mirror. Knausgaard begins the scene explaining his reasons for the act, so he doesn’t need to address them while he’s doing it. The writer might mistakenly note the narrator’s thoughts of Linda while the cutting is happening.

Knausgaard excels here because of his honest portrayal of the narrator’s interiority, and the readers reward him with their attention. The events that lead the narrator to cut up his face produce an anger in him that leads to the action, and during the action, the anger takes over completely; therefore, the act is removed from its rational context. You know how it feels to spiral out of control, go crazy for a couple minutes, and eventually forget why you were feeling that way in the first place?

The objects Knausgaard chooses to describe, too, are subtle and carefully chosen with fidelity to realistic first-person narration. When he enters the bathroom and cuts himself, here are the only objects mentioned: the glass, the sink, the wall, the shard, the face (chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, underneath the chin), the towel, the blood. That’s it. The reader’s brain fills in the rest, but when listed in that order, the reader can put together what happens without even needing anything else. Imagine if Knausgaard had chosen to over-describe the shower curtain, the squeaking door, the medicine cabinet latch that was slightly off-kilter. What could you gather from that?

This is relevant because it reveals both how Knausgaard is able to enhance the action through description and be authentic to the interiority of his narrator. And it’s just one example of My Struggle’s success. Knausgaard also successfully speaks through himself as a pre-adolescent child in Book 3, after opening the book by revealing that there’s absolutely no way he would have firsthand memories of any events in the book. He never crosses the line into another character’s interiority—even his wife’s, the main object of his thoughts throughout the books—and keeps the interiority between the narrator (Knausgaard at whichever age he is in the plot) and the writer (Knausgaard as he presents himself currently writing). He fits a very rich and well-written 400-page essay on Paul Celan’s poem “Death Fugue” and Hitler’s rise in the middle of a book that had been, to that point, largely about his own legal struggles. And while drama and gossip are far from the main objective of these books, he doesn’t shy away from domestic tension.

When a novel this uniquely accessible, well-written, and addictive spans six volumes and nearly 4,000 pages, it becomes hard to read anything else afterwards. After My Struggle, I would try so hard to be wholly gripped and consumed by a book, and it just didn’t happen. Maybe I chose the wrong books. Maybe I was burned out. Maybe I became overtaken by Knausgaard’s style, or his world, or his life, or his narration, or his writing. I think it was all of those things.

I’m a fan of big, challenging books. I like the avant-garde bullshit that some people reject outright. If a book is criticized for “punishing its reader,” or for messing around with too many characters or plot threads, I may still want to read it. I’m usually, also, not the biggest fan of straightforward realism, books in which the author intentionally stays in bounds and lets the characters/plot do all the work. Sometimes I like to be winked at.

But once I finished My Struggle, I had an incredibly hard time getting readjusted. I tried Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, a book that seems to check all of my boxes, and yet it’s now sitting on my shelf, three-quarters read. As is Melancholy I-II by Knausgaard’s own former teacher Jon Fosse. I ditched formally groundbreaking stuff and read a couple books by Bret Easton Ellis, which I enjoyed but left me pretty unsatisfied. I read Blake Butler’s memoir Molly, which was devastatingly sincere and terribly depressing, but despite its formal similarity to My Struggle, I just couldn’t get myself fully attached. Same with Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy. While I’ll certainly go back to these great books, I can’t say they had the same immediate impact on me as Knausgaard’s.

It’s been close to a year since I finished My Struggle, and I still haven’t found a book that’s gripped me the way Knausgaard did. I’ve never been to Norway or Sweden, never even met anyone from Norway, know an extremely limited number of Scandinavian people, and usually never even looked up the places Knausgaard described. Yet the books are so intensely interesting that I can still picture my mentally constructed image of Knausgaard’s apartment in Mälmo, his father’s cluttered house, his childhood home on Tromøya, the grocery store he shops in with Heidi and Vanja, the classroom in which he first met Linda, and many other locations. I could sit down with someone else who’s read the book and say “Remember that time when Knausgaard did this,” or “said this?”

It’s not a flaw that Knausgaard wanted to break novelistic tradition to make his work more visual. It’s actually a major success and largely responsible for all the hype behind his books. Again, I enjoy books that are commentaries on form, books whose characters double as recontextualizations of other characters, whose plots are constructed to tear down other plots, whose chronologies are rearranged to reject straightforward timelines. But there is something so refreshing about My Struggle narrowing the distance between fiction and reality, building up a world inside and outside the author’s consciousness, offering up to readers the life of one man for close to 4,000 pages of clean, accessible prose.

I don’t know of any other book that has this combination of features. And it’s been very, very hard to find a book that will have a similar impact on me.

I now want to read this book

Interesting 🤔